As shown in the above print by John Leech, the rick

burners were impoverished, and rebelled by burning

ricks of hay. (This is explained in greater detail

in the discussion of the Industrial Revolution).

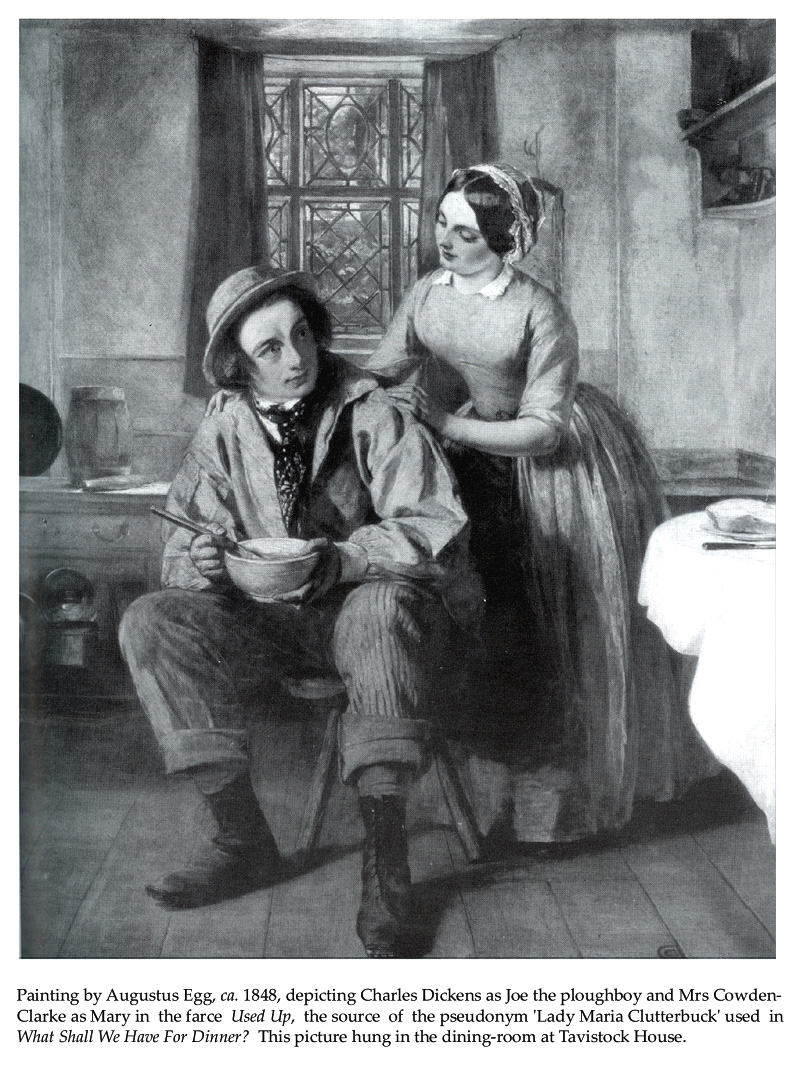

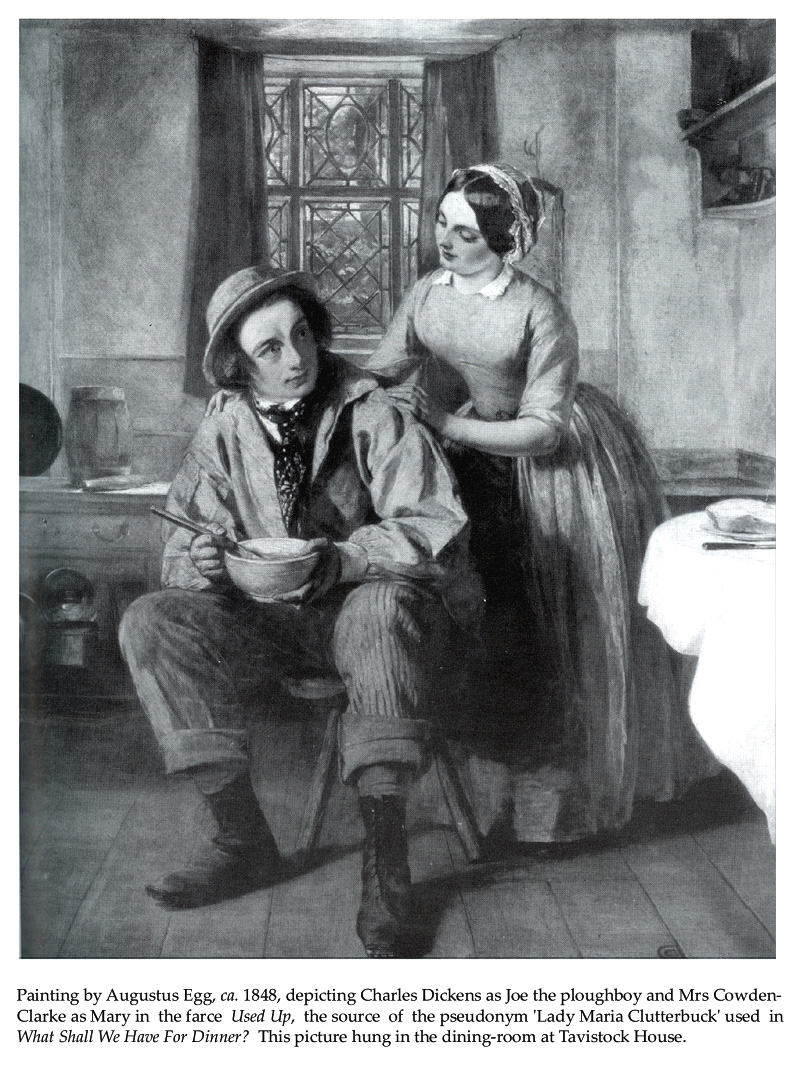

The painting of Dickens by Augustus Egg shows an interest

Dickens shared with others. Dickens was closely in touch

with John Leech, Augustus Egg, Henry Mayhew, etc.

The next contradiction with Mayhew's very careful

reporting of a dredgerman's testimony, is Dickens'

introduction of Gaffer Hexam's daughter Lizzie, who

rows their boat as Gaffer scans the water for likely

items to scavenge (bodies). Lizzie expresses a view

that is in sharp contrast with the epitome of his life

given by the dredgerman in "London Labour and the

London Poor". It is highly unlikely that anyone

living from hand to mouth on the river would hold such

a view, but it is exactly what we would expect Charles

Dickens, with his bourgeois attitude, to impute to

others:

.

"Here! and give me hold of the sculls. I'll take the rest of

the spell."

"No, no, father! No! I can't indeed.

Father!—I cannot sit so near it!"

He was moving towards her to change places, but her

terrified expostulation stopped him and he resumed

his seat.

"What hurt can it do you?"

"None, none. But I cannot bear it."

"It's my belief you hate the sight of the very river."

"I — do not like it, father."

"As if it wasn't your living! As if it wasn't meat and

drink to you!"

At these latter words the girl shivered again, and for

a moment paused in her rowing, seeming to turn deadly

faint. It escaped his attention, for he was glancing

over the sterm at something the boat had in tow.

"How can you be so thankless to your best friend,

Lizzie? The very fire that warmed you when you were

a babby, was picked out on the river alongside the

coal barges. The very basket that you slept in, the

tide washed ashore. The very rockers that I put it

upon to make a cradle of it, I cut out of a piece of

wood that drifted from some ship or another."

Charles Dickens, "Our Mutual Friend", Penguin edition, p. 15

.

Note that in the passage above, the view presented

is that the dredgermen dredged coal from alongside

the coal barges (either from coal spilled in the

water or through theft of coal directly from the

coal barges). Once again, Mayhew's information is

far more precise: "I know a furrow off Lime'us Point,

no wider nor the dredge, and I can go there, and what

others can't git anything but stones and mud, I can

git four or five bushels o'coal. You see, they lay

there, they get in with the set of the tide, and can't

git out so easy like." No mention of theft. It is

quite possible that some dredgers did steal coal, but

it is also evident that some dredgers did not

steal coal.

.

Mayhew also points out that when a dredger gets too

old to dredge he still works for a living, at jobs

such as "scrapin'" (scraping off the old tar from

ships with a scraper). Even in old age, there is no

sign of begging or theft.

.

Dickens reinforces the idea that Gaffer Hexam "stole"

money from the dead man's person in another passage.

Rogue Riderhood accuses Gaffer Hexam:

.

"Since when was you no pardner of mine, Gaffer Hexam Esquire?"

"Since you was accused of robbing a man. Accused of

robbing a live man!" said Gaffer, with great

indignation.

"And what if I had been accused of robbing a dead

man, Gaffer?"

"You COULDN'T do it."

"Couldn't you, Gaffer?"

"No. Has a dead man any use for money? Is it possible

for a dead man to have money? What world does a dead

man belong to? 'Tother world. What world does money

belong to? This world. How can money be a corpse's?

Can a corpse own it, want it, spend it, claim it, miss

it? Don't try to go confounding the rights and wrongs

of things in that way. But it's worthy of the sneaking

spirit that robs a live man."

Charles Dickens, "Our Mutual Friend", Penguin edition, p. 16

.

The passage above is in direct opposition to Mayhew's

statement that "the dredgers cannot by reasoning or

argument be made to comprehend that there is anything

like dishonesty in emptying the pockets of a dead man."

In fact, "They say that anyone who finds a body does

precisely the same, and that if they did not do so the

police would." Thus, not only do dredgers in general

not feel that emptying the pockets of corpses is

dishonest, but they feel as if they are acting

as lawfully as

the police. In crafting a conversation where one

dredgerman questions another about the morality of

removing money from a corpse's pockets, Dickens inserts

his own comforting bourgeois view of law and honesty in

place of the reality of what law and honesty really mean.

.

Dickens portrays Gaffer Hexam both as a man who

is capable of reading (which seems unlikely), and as

a man who is opposed to formal education. This at least is in line with

what Mayhew wrote in his interview with a dredgerman,

whom he quotes as saying "There's on'y one or

two of us dredgers as knows anything of larnin', and

they're no better off than the rest. Larnin's no good

to a dredger, he hasn't got no time to read".

.

Taking up the bottle with the lamp in it, he

held it near a paper on the wall, with the

police heading, BODY FOUND. The two friends

read the handbill as it stuck against the wall,

and Gaffer read them as he held the light.

"Only papers on the unfortunate man, I see," said

Lightwood, glancing from the description of what

was found, to the finder.

"Only paper."

Here the girl arose with her work in her hand, and

went out the door.

"No money," pursued Mortimer; "but threepence in

one of the skirt-pockets."

Charles Dickens, "Our Mutual Friend", Penguin edition, p. 31

.

"One of the gentlemen, the one who didn't speak

while I was there, looked hard at me. And I was

afraid he might know what my face meant. But

there! Don't mind me, Charley! I was all in a

tremble of another sort when you owned to your

father you could write a little."

"Ah! But I made believe I wrote so badly, that it

was odds if any one could read it. And when I wrote

slowest and smeared out with my finger most, father

was best pleased, as he stood looking over me."

Charles Dickens, "Our Mutual Friend", Penguin edition, p. 36

.

Upon what sources did Dickens draw, in the creation of

the character of Gaffer Hexam? Although there is no direct

evidence that Dickens was familiar with the work of Henry

Mayhew, it is difficult to believe that Dickens was unaware

of it.

.

... Mayhew's interviews with London street folk were well

enough known for Dickens to have been aware of them whether

he knew Mayhew or not. Mayhew first told well-off readers of

the shifts by which the poor of London stayed alive from one

day to the next in the Morning Chronicle in 1849-1850.

The work appeared in a bewildering variety of amended,

augmented, edited, and reorganized editions during the next

dozen years and more. ... [T]he final version of the work was

printed in 1864 and again in 1865. Dickens was writing

Our Mutual Friend in 1864 and 1865; it would be strange

if he did not know something at least about material so

relevant to his interests ...11

.

.

Three interests of Dickens are relevant here: his affection

for the Thames, his fascination with the work of the police,

and a longstanding interest in drowning.12

.

Harlan Nelson has studied the relationship between

Henry Mayhew's "London Labour and the London Poor"

and Charles Dickens' "Our Mutual Friend", and

has noticed other striking coincidences, as follows:

.

[T]he relationship with

London Labour and the London Poor becomes

still more plausible on the discovery of two other

passages in Mayhew. One contains touches suggesting

Gaffer Hexam, the dredgerman (river scavenger) in

Our Mutual Friend, touches that include

distinct verbal reminisces and parallel details.

The other is an extensive section on London dustmen

and the garbage they collected, matter that

(considering the use made of dust and the dust trade

in Our Mutual Friend), certainly would have

caught Dickens's eye, if indeed it was not what drew

his attention to the book in the first

place.13

But there is yet another circumstance that argues for

the relationship I have suggested between

London Labour and the London Poor and

Our Mutual Friend. In a work running to

nearly six hundred closely printed pages, the

passage about the dredgermen occurs only four pages

after the one dealing with the old

woman14, and

only nine pages before the section on dust begins;

so that not only does a methodical reader, but a

browser, or a skimmer, or a novelist looking for

material, would be likely to run across all of them.

It was while browsing, in fact, that I discovered

these passages myself.15

Conclusion

In conclusion: it does appear that Dickens has at least

borrowed ideas about dredgermen from the research that

Henry Mayhew published several years before Dickens

published "Our Mutual Friend", but not quite.

Dickens replaced much of the facts found by Mayhew

with Dickens' own bourgeois imagination about law,

morality, and education: ideas with which Dickens was

more comfortable.

.

1

"Nineteenth-Century Fiction", Vol. 24, No. 3,

Dec. 1969, pp. 345-349, ""Dickens and Mayhew:

A Further Note", by H. P. Sucksmith.

.

2

"Dickens certainly knew of Mayhew as a writer as

early as 1838 for while editing "Bentley's

Miscellany" He had published a piece of

comic fiction entitled 'Mr. Peter Punctilio,/

The Gentleman in Black'" by Henry Mayhew.

Ibid., p. 346.

.

3

"Mr. and Mrs. Charles Dickens Entertain at Home",

by Helen Cox, Pergamon Press, 1970, pp. 130, 150, 158, 170.

.

4

"The Other Nation: The Poor in English Novels of the 1840s

and 1850s", by Sheila M. Smith,

Oxford University Press, Oxford, Great Britain,

1980, p. 166.

.

5

"[Mayhew] stops talking and lets the child speak, with

the authentic voice ... . Listening to her, we

realize what Dickens and Collins meant by their phrase

'strikes to the soul like reality'. From her words we

get the same kind of direct impact of her life as we

get from [a] remarkable photograph ... and as we do

not get from, say, Dickens's Sissy Jupe." Ibid., p. 167.

.

6

"The Victorian Novelist: Social Problems

and Social Change", Edited by Kate Flint,

Croom Helm, New York, N. Y., 1987, pp. 226-229.

.

7

A "waterman" is licensed to carry passengers.

A "lighter" carries goods or baggage, only. A

"dredgerman's" boat is equipped with grappling

hooks, and ropes and typically carries scavenged

coal, bones, rope, metal or any other object

with value, including dead bodies.

.

8

"London Labour and the London Poor",

by Henry Mathew, London, 1861-1862,

II, pp. 149-150.

.

9

Mayhew's dredgers pick up many things besides

bodies—finding a body, which means a fixed fee

("inquest money") and perhaps a reward, is occasionally

and outside the routine of their regular business.

Dickens's Hexam seems to have little interest in anything

else. "Dickens's OUR MUTUAL FRIEND and Henry Mayhew's

London Labour and the London Poor", by Harland S.

Nelson, Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 20, #3, Dec. 1965,

p.221.

.

10

Dickens correctly invokes the desired gothic mood, at the cost of

inaccuracy. See "BIRDS OF PREY: A STUDY OF OUR MUTUAL FRIEND",

by R. D. McMaster, The Dalhousie Review, vol. 40, 1960, p. 373.

.

11

"Dickens's Our Mutual Friend and Henry Mayhew's London Labour

and the London Poor", by Harland S. Nelson, Nineteenth Century

Fiction Vol. 20 (3), December 1965, p. 213.

.

12

"[Dickens] had a preoccupation with the river, and

drowning, that came near being an obsession: not

to speak of its role in his fiction, it appears

in a number of his periodic articles. In one of these,

"Down with the Tide" (Household Words, February 5,

1853...), the subject is handled more lightly than usual,

even whimsically. But that article interests me just here

for another reason, too. It is one of a series Dickens did

on the police, whose work fascinated him and whose

expertise drew his admiration. In this one Dickens reports

on a river patrol he took with the Thames Police. We get

an interview with the toll collector at Waterloo Bridge,

full of macabre drollness (the man's cheerful precision

about the habits of prospective suicides), and an account

of the various sorts of scavengers that the police keep an

eye on and among these, Dickens gives some space to dredgermen.

But there is not a word about their work of recovering

bodies, or about their peculiar perquisites—omissions

doubly odd if Dickens knew about these matters, considering

his persistent interest in drownings, and the prominence of

suicide by drowning in this particular piece.

.

"But having written about dredgermen himself Dickens would

probably notice them the more readily later in the writings

of others; and their macabre salvage activity, as reported

by Mayhew, would certainly recommend them to his

attention." [Ibid., p. 219]

Web Site Terms of Use

Web Site Terms of Use